Introduction

Augustus (63 BCE- 14 CE) is generally considered to be the first Roman emperor, who instituted a new ideological system for empire that lasted for three centuries. By the mid to late first century BCE, the ravages of decades of civil war resulted in a beleaguered Roman state eager for change and stability. Octavian’s promise was a return to religious observance and morality, an end to civil war, the continued expansion of the empire, and peace and prosperity for the Roman people. From his consulships of 31 BCE through to 23 BCE, to his acceptance from the senate of many honours (including proconsular imperium and the name Augustus) in 27 BCE, Octavian/ Augustus stealthily attained power, resulting in a ‘system monarchical in all but name’ (Beard & Crawford, 1985: 1). In my previous post ‘T. Carisius- a very special coin’ we encountered the propraetorian legate Publius Carisius, whose tour of duty in the Cantabrian Wars was between 26 and 22 BCE (Labrador et al, 2019: 433). A series of coins produced to celebrate the Roman victory in Spain around 25-23 BCE are worth analysing in more detail to provide us with a view of Roman conquest in general and Augustan propaganda in particular.

The Coins

The first coin to be discussed is a denarius which demonstrates the bare head of Augustus on the obverse and on the reverse there is a circular shield with a central boss and the legend IMP (above) CAE SAR (at sides) and DIVI. F (below) (Figs. 1 & 2). Augustus is therefore depicting war like imagery in commemorating the Roman victory in Spain as well as announcing his status as son of the god Julius Caesar. This helped to legitimise his right to rule and in addition formed a connection between himself and his father in terms of their successes in Roman conquest.

The second coin to be considered is a denarius depicting the bare head of Augustus with the legend IMP CAESAR AVGVST on the obverse and a Trophy depiction on the reverse, with the inscription P CARISIVS LEG PRO PR (Figs. 3 & 4). A trophy was a symbol of Roman victory where the defeated army’s weaponry was displayed in a procession- in this case, a central helmet, cuirass and shield, surrounded by javelins, shields, lances and other arms. P. Carisius was also being proclaimed propraetorian legate of the Emperor, a high ranking general who had previously held consular or praetorian rank.

This coin was therefore both a celebration of the Roman conquest of this area of Spain, with Augustus firmly declaring himself Emperor, and a celebration of Publius Carisius as his military commander: a powerful symbol of Roman propaganda.

The third coin to consider is an as, a copper coin (1 silver denarius = 16 copper asses) (Figs 5 & 6). On the obverse, Augustus with the inscription CAESAR AVG IC POTEST is proclaiming himself emperor with tribunican power, an important office which would be adopted by future emperors, becoming an essential feature of imperial rule. The inscription on the reverse P. CARISVS LEG AUGVSTI declares simply that P. Carisius is the legate of Augustus.

In summary, these three coins can be considered to be powerful tools of propaganda, both in Rome and throughout the empire, commemorating the defeat of the Cantabri and Asture tribes of Northern Spain. Augustus is declaring himself son of a god and legitimate leader of the Roman people, with Publius Carisius being endorsed as the Roman commander who was the right-hand man of Augustus in accomplishing this conquest.

Historical Background

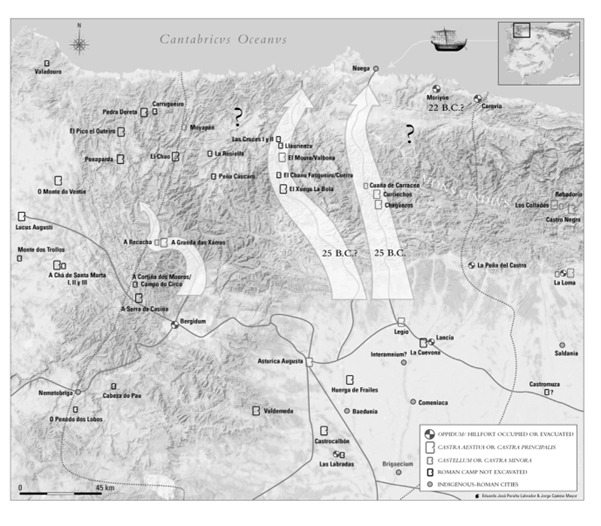

Labrador et al (2019: 421) note that the Cantabrian wars were an attempt by Augustus to finally settle the long conquest attempted by Rome over the preceding two centuries. A resistant enclave consisting of two tribes, the Cantabri and the Astures, existed in the mountainous area in Northern Spain. It is thought that this area was attacked from the south by at least three Roman legions (Fig. 7).

When these troops reached the coast in 25 BCE a Roman victory was declared, and was celebrated with acts such as the minting in Spain of the P. Carisius coins and the closing of the temple of Janus in Rome (Hornblower & Spawforth, 1998). The doors of the Temple of Janus in the Roman Forum were symbolically opened during times of war and closed during times of peace, and this was the second time Augustus achieved this, the first being subsequent to his triumph over Antony and Cleopatra in 29 BCE. Augustus was therefore sending a strong message to the Roman people in 25 BCE, presenting his victory in Spain and ensuing Roman peace as a fait accompli. However, there were significant uprisings in 22, 19 and 16 BCE. Cassius Dio documents the 22 BCE uprising of the Cantabri and the Astures, noting the ‘luxurious ways and cruelty’ of Carisius. The rebellion and subsequent subjugation is described in chilling terms:

‘Not many of the Cantabri were captured; for when they had no hope of freedom, they did not choose to live, either, but some set their forts on fire and cut their own throats, and others of their own choice remained with them and were consumed in the flames, while others yet took poison in the sight of all. Thus most of them and the fiercest element perished. As for the Astures, as soon as they had been repulsed while besieging a certain stronghold and had later been defeated in battle, they offered no further resistance, but were promptly subdued’.

(Cassius Dio, Roman History, 54.5)

To conclude, these coins represent Augustus’s attempt to both legitimise his position and celebrate his military conquest in the crucial early stages of his rule. However, given the later uprisings, an important question should be asked: was a this a naively premature celebration of victory? or a cynical attempt to deceive? Given Augustus’s extensive military experience, much of it obtained in the provinces, the potential for continued unrest could not have been ignored. The P. Carisius series of coins give the impression of an emperor eager to exaggerate his military conquest and disseminate this propaganda throughout the Roman world. They also reflect the juxtaposition of the cruelty of P. Carisius to these conquered peoples and the celebration of his military prowess throughout the Roman Empire.

Bibliography:

Ancient Sources:

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Earnest Cary (trans.) [Online]. Available at https://search.app/v5ZDbw25j3HWaSg1A (Accessed 5 September 2024).

Modern Sources:

- Beard, M., Crawford, M. (1985) Rome in the Late Republic, 2nd. Edition, Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

- Hornblower, S., Spawforth, A. (1998) The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Labrador, E., Mayor, J., Torres- Martinez, J. (2019) ‘Recent research on the Cantabrian Wars’, Journal of Roman Archaeology, Vol. 32, pp. 421-438 [Online]. Available at https://www-cambridge-org.ezproxy1.lib.gla.ac.uk/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/4CAA0D7E080AE9597C6E6E0C224EF0C1/S1047759419000217a.pdf/recent-research-on-the-cantabrian-wars-the-archaeological-reconstruction-of-a-mountain-war.pdf (Accessed 21 September 2024).

Leave a Reply to Fraser Cancel reply