Introduction

This Roman Republic coin is one of the most interesting coins from antiquity in that it depicts the implements used in striking ancient coins and consequently stimulates debate on the workings of the Roman mint itself. In addition, it is an interesting coin to consider in relation to the social and political context of the late Roman Republic.

The Coin

On the obverse of the coin (Fig. 1), a female bust is depicted wearing a necklace and earrings and her hair tied in a bun with a loose ribbon. The inscription MONETA is behind her head, and the coin is bordered by a row of dots.

So, who is Moneta? This is Juno Moneta, goddess of the Roman mint. Juno was queen of the gods and wife to Jupiter (counterparts to Hera and Zeus in Ancient Greece). Juno had various manifestations, such as Juno Lucina (the deity of childbirth), Juno Sospita (the war goddess), Juno Conservatrix (Juno the Preserver), Juno Martialis (mother of Mars, the god of War) and Juno Moneta (goddess of the Roman mint). Another important deity in Roman coinage was the blacksmith god Vulcan, the equivalent to the Greek god Hephaestus.

On the reverse (Fig. 2), there is a pair of tongs, an anvil and a hammer depicted from left to right. On top of these is a garlanded object, and at the top is the inscription T. CARISIVS. There is a laurel-wreath border.

Discussion

Where was this coin produced and by whom? This silver denarius was issued in 46 BCE by the moneyer Titus Carisius, about whom little is known. At this time he was a junior magistrate in the intensely competitive political world of the Roman Republic, termed the cursus honorum (Fig. 3). Along with two other magistrates (Cordius Rufus and Caius Considius) he would have been responsible for the Roman mint for the period of a year, thus having the beneficial effect of raising his political profile.

In ancient Rome, the mint was located in (or close to) the Temple of Juno Moneta on the Capitoline Hill, which was also the location of the Roman treasury at that time. Little is known about how exactly Roman coins were produced, as no written sources exist which describe the procedure- hardly surprising given the sensitive nature of the process and the need to guard against forgeries. Ancient mints have been excavated and provide some clues, although the actual processes remain elusive. Reverse archaeology can provide us with some possibilities, and modern scientific innovations are increasingly revealing these secrets (Ponting, 2012: 12-30). In basic terms, the process of striking coins involves heating up metal disks to a high temperature where they would be struck between two dies on an anvil. Tongs would be used to position the metal between the two dies, and struck with a hammer. This is obviously an imperfect system, subject to the skill of the blacksmith, and is why ancient coins can be off centre or poorly struck. This was a creative team of artistic die engravers and skilled craftsmen, composed of freedmen and slaves, who unfortunately remain largely anonymous to us in modern times. One Roman inscription by an imperial freedman named Felix in 115 CE documents that he was an overseer in the Roman mint, and that the team of 63 workers was composed of equal numbers of slaves and freedmen (CIL VI.44).

The Debate

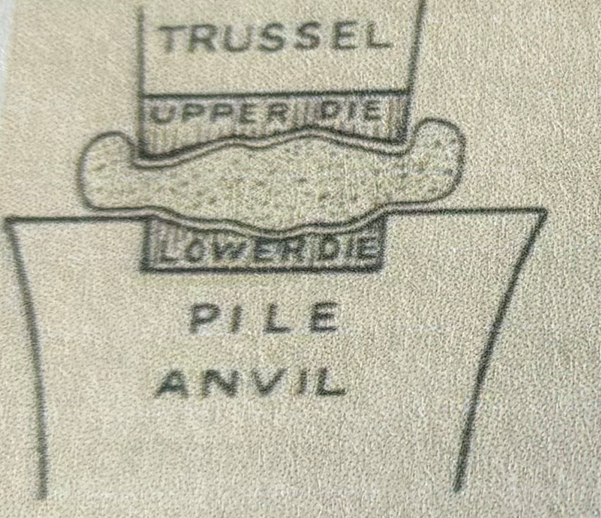

The garlanded object is a source of much debate in the numismatic world: some numismatists consider this to represent an upper punch die (Crawford, 1975; Sear, 1988) but others consider it representative of the headwear that mint workers might have worn, similar to the cap of Vulcan (Fig. 4) (Numismatics International, 2022). Compare this to the depiction of the pileus, the freedman’s cap, demonstrated in Figure 5. Alternatively, this object could feasibly represent the trussel into which the upper die was inserted (Fig. 6). At present, numismatic opinion is divided between the cap of Vulcan theory and the punch die theory, with the majority favouring the cap theory (Numismatics International, 2022).

T. Carisius is thought to have been a supporter of Julius Caesar in the civil wars and this issue was probably struck to pay the army of Julius Caesar’s recent quadruple triumph over Gaul, Pontus, Africa and Egypt. Numismatists note that this series is often lightly struck, possibly due to a hasty production process. Is this the result of the sudden demand for an enormous amount of coinage necessary to pay for Caesar’s troops on their return from their quadruple triumph? This would seem likely: the Roman historian Appian (History of the Civil Wars, 2.101- 2.102) tells us that Caesar exceeded his promises in terms of payments to his soldiers, giving each basic soldier 5,000 denarii, double the amount to centurions and double again to each military tribune and prefect, and 100 denarii to each member of the Plebs. Given that many Roman legions were involved in these conquests, with each legion being composed of 4-6,000 soldiers, a vast quantity of coinage would have been required by Caesar in a short timescale.

T. Carisius is subsequently lost to our historical record, but is credited in some circles as being the same Roman legate who defeated the Astures in Hispania around 25 BCE, the Astures revolting against him in 22 BCE due to his ‘cruelty and insolence’ (Numismatics International, 2022). However, this point is debatable given that Augustus celebrated his legate P. Carisius at this time and it seems likely that this was in fact another family member, possibly the son of T. Carisius (Labrador et al, 2019: 423; Magie, 1920: 338) (Figs. 7&8).

Conclusion

To conclude, the coin of T. Carisius allows us to consider the religious and societal importance of the mint of the Roman Republic as well as Roman socio-political policy in this important period in the late Republic. We are also reminded that while we may know much of life in the Roman world, there are still gaps in our knowledge, leading to debate, conjecture and speculation.

Bibliography:

Ancient Sources:

- Appian, History of the Civil Wars, John Carter (trans.)[Online]. Available at https://search.app/GKAA5QVzr1UFAGzf9 (Accessed 19 September 2024).

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Earnest Cary (trans.) [Online]. Available at https://search.app/v5ZDbw25j3HWaSg1A (Accessed 5 September 2024).

- Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarium VI. 44 [Online]. Available at https://search.app/ouU4kmVyT6JweYmw9 (Accessed 2 September 2024).

Modern Sources:

- Crawford, M.H. (1975) Roman Republican Coinage, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Harney, G. (2024) Moneta: A history of ancient Rome in twelve coins, Penguin, London.

- Labrador, E., Mayor, J., Torres- Martinez, J. (2019) ‘Recent research on the Cantabrian Wars’, Journal of Roman Archaeology, Vol. 32, pp. 421-438 [Online]. Available at https://www-cambridge-org.ezproxy1.lib.gla.ac.uk/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/4CAA0D7E080AE9597C6E6E0C224EF0C1/S1047759419000217a.pdf/recent-research-on-the-cantabrian-wars-the-archaeological-reconstruction-of-a-mountain-war.pdf (Accessed 21 September 2024).

- Magie, D. (1920) Augustus’ War in Spain (26-25 BC) Classical Philology, 15(4), pp.323-339. [Online]. Available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/360305 (Accessed 5 September 2024).

- Numismatics International, May 2022, [Online]. Available at http://numis.org/coins-of-the-month/may-2022-spotlight/ (Accessed 2 September 2024).

- Ponting, M. (2012) ‘The Substance of Coinage: The Role of Scientific Analysis in Ancient Numismatics’, in William E. Metcalf (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage, Oxford Handbooks, Oxford.

- Sear, D. (1988) Roman Coins and their values, 4th. Revised Edition, Seaby Publications Ltd., London.

Leave a Reply