Introduction

Roman baths were ubiquitous throughout the Roman Empire during a period of many hundreds of years, a testament to their importance to Roman culture and identity. In the modern world we can marvel at the large scale magnificence of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (Fig. 1) or the understated functionality of the bathhouse at Chesters Fort near Hadrian’s Wall (Fig. 2), and appreciate the architectural legacy left for us. However, the social aspects of bathing have proved to be more elusive to determine, such as who in particular bathed and why. Was bathing an exclusively male pursuit? Did females have access to bathing, and if so, did mixed bathing exist? Did slaves bathe? And of course, there is the consideration of the cost; was bathing accessible to only those who could afford it? In teasing out the social history of Roman bathing, careful analysis of evidence in addition to architecture, such as inscriptions, mosaics, literature, and even graffiti, is required.

Male or Female?

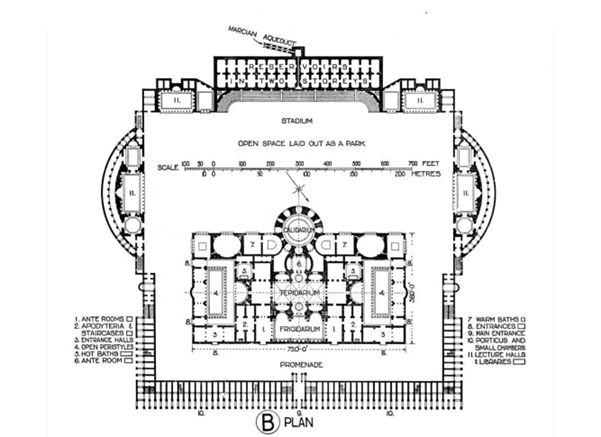

In considering our first question of whether bathing was an exclusively male pursuit, we can look for clues in the architecture of the buildings themselves. The dual design of the Baths of Caracalla certainly gives an indication of the potential for segregated bathing. However, several rooms, such as the frigidarium, tepidarium and caldarium, are single indicating that some rooms may have been mixed, or sexes may have bathed at different times (Fig. 3). Note also the presence of a stadium, as well as lecture halls and libraries. On Architecture, by the Roman architect Vitruvius, comprehensively informs us of many aspects of Roman architecture, including baths (Hornblower et al, 1998). Vitruvius specifically mentions that the hot baths for men and women should be adjacent to each other and planned with the same aspects in terms of making use of natural topography thus providing evidence of female bathing. It is clear that this architect at least considered that bathing should be segregated.

And what is the evidence for mixed bathing? The satirical poet Martial (38-104 CE approx.) writes extensively of mixed bathing. Satirical literature should generally be treated with caution, as by definition, they are prone to exaggeration. However, although Martial satirises women for various reasons, such as expressing a sexual interest in him yet refusing to share a bath, he does not satirise their presence at mixed bathing (Fagan, 2005). There is, however, evidence that bathing was often separate, either in different establishments (often found close together) or at different times (Nielsen, 1990). One view is that the fashion for mixed bathing changed over time. The preponderance of separate wings in the Republican period, and absence of such in the Imperial era can be interpreted as mixed bathing being unpopular in the Republic, then accepted in the early Empire, and then becoming unfashionable again, with the ban on mixed bathing by Hadrian (117-38 CE) and later Severus (222-35 CE). The time scales involved indicates the persistence of the problem, and the fact that Emperors banned it indicates that it may have been widespread throughout the Empire. It seems likely that mixed bathing was acceptable in certain areas or even in certain establishments, and at certain times over the course of many hundreds of years (Fagan, 2005).

Who could access?

Our next question is whether poorer members of society could access bathing. There is ample evidence that the elite used public baths, such as Pliny advising of the convenience of the public baths in the village near his Laurentum villa (Letters 2.17), and even the Emperor Hadrian, who seemed keen to pursue an image of an Emperor with the common touch (Scriptores Historiae Augustae). The plethora of public baths in Rome would certainly suggest that bathing was widespread and therefore accessible to the poorer in society. The sheer size of the larger establishments, such as the Baths of Caracalla, indicate that were obviously designed to accommodate large volumes of people. Pliny the Elder advises that Agrippa, the lifelong supporter of Augustus, who is known to have carried out popular restoration and building works, opened the bathing establishments free of charge in celebration of building work he had carried out during his aedileship (Natural History 36.121-123). This source is particularly useful for two reasons: the first is that the number of bathing establishments is quantified as 170 during Agrippa’s aedileship during 43-40 BCE (Hornblower and Spawforth, 1998). Pliny the Elder describes the number of baths as having ‘infinitely increased’ during his lifetime of 23-79 CE. The huge numbers of baths in Rome during these times is evidence that bathing was highly unlikely to have been a purely elite pursuit. The second point to consider is that there was a charge for entry to bathing establishments. It seems likely that costs would have varied, and that bathing was accessible to all but the poorest in Roman society, who could still, on occasion, access bathing in times of celebration when it was free.

In considering whether slaves had access to bathing, a variety of evidence places slaves at the baths as attendants to their masters. The fact that smaller baths had benches outside has been postulated as an indication that slaves could wait here for their master (Fagan, 2005). The potential for the enterprising Roman is not to be missed, and papyri from the Roman town of Oxyrhynchus in Egypt reveal that the changing room with its boxes for clothes were leased out, the lease holders recovering their rent in fees (Parsons, 2007).

The Piazza Armerina mosaic depicts a group of bathers entering baths (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, depictions on mosaics are subject to individual interpretation, and it is impossible to be certain, but some of the group are believed to be slaves carrying towels and bath related instruments.

A useful source of information of Roman life in general is that of school textbooks (colloquia) from the late Imperial period, which instruct the young elite Roman on the necessary protocols of everyday life, and therefore considered to be valuable sources. In this case, they helpfully provide us with evidence that young elite Romans had expectations of bathing with a slave retinue and were given standard commands to deal with them (Fagan, 2005).

Having established that slaves could attend the baths as attendants, the next question to ask is; could slaves have attended the baths as customers? An important caveat to consider is that certain slaves would have had limitations imposed upon them by their particular duties. Thus slaves working in mines we would reasonably expect to have little opportunity to use public baths, whereas those higher in the slave hierarchy, such as slaves to the emperor, may have had more opportunity. Martial makes direct reference to a slave bathing with a master: ‘Your slave goes into the bath with you, Caelia, covered with a brass sheath…’ (Epigram 11.75). It is, unfortunately, impossible to differentiate whether this slave was present as an attendant or using the facilities separately from his duties. Throughout literature, there are various hints of slaves as independent customers of baths, for example, when a guest of Martial arrived too early and he had to send for his slaves who were at the baths, and Juvenal, whose slave underwent depilation, indicating recreation rather than service (Fagan, 2005). Another piece of evidence is a graffito from the Suburban Baths in Herculaneum. Apelles, a slave of high imperial status, wrote of a pleasant visit to the baths, where he lunched and had sex. This evidence, as well as attesting to the fact that slaves could visit the baths for recreation, also indicates some services other than bathing and exercise that establishments could provide, in this case food and prostitution.

Conclusion

To conclude, female bathing can be considered to be customary practice, whereas mixed bathing seems to have been subject to particular fashions over time periods, areas, and possibly individual establishments. In discussing whether the poor and slaves could bathe, we can see that the sheer number of luxurious thermae and more modest privately owned balnea, as well as the limited written evidence we have available to us, indicates that bathing was not just an elite pursuit and was a typical custom for poorer Roman citizens. There is evidence that slaves would typically attend baths as attendants to their masters, but the evidence for recreational bathing for slaves is somewhat weaker, and was likely to be hierarchical in nature, a high status slave likely having more opportunity than, for example, an agricultural or mining slave.

Our analysis has also revealed the ancillary aspects of a trip to the baths: exercise, libraries, food consumption and prostitution could all be accessed, ensuring an enjoyable and socially cohesive experience for the average Roman.

Bibliography

Ancient Sources:

- Martial, Epigrams, Shackleton Bailey, D.R. (ed. and trans.) (1993) Martial: Epigrams, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- Pliny, Letters, Radice, B. (trans.) (1969), The Letters of the Younger Pliny, London, Penguin.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Eichholz, D. (trans.) (1971) Pliny: Natural History, London, William Heinemann.

- Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Magie, D. O’Brien- Moore, A., Ballou, S. (eds.) (1921) [Online]. Available at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:2008.01.0508 (Accessed 25 August 2024).

- Vitruvius, On Baths, Granger, F. (ed. and trans.) (1962) Vitruvius: On Architecture, London, William Heinemann.

Modern sources:

- Fagan, G. (2005) Bathing in Public in the Roman World, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, pp.12-39.

- Hornblower, S. and Spawforth, A. (1998), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (2nd edn), New York, Oxford University Press.

- Nielson, I. (1990) Thermae et Balnea: The Architecture and Cultural History of Roman Public Baths, Vol.1, Aarhus, Aarhus University Press.

- Parsons, P. (2007) City of the Sharp-Nosed Fish: Greek Lives in Roman Egypt, London, Phoenix.

Leave a Reply to Andrea Cuthbertson Cancel reply