Introduction

Athens in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE was a well-ordered democracy with a sophisticated legal system. The major tasks of policing- investigation, apprehension, prosecution and enforcement- were carried out by the citizens themselves. A citizen charged with an offence would be able to plead his case in front of a court composed of citizen jurors, where a verdict would be reached on the basis of a majority decision. Unfortunately, no written evidence remains of these ancient laws, but we do have the works of the Attic Orators, who were speech writers from this period. There was no legal representation in court in these days, so the citizen was expected to represent himself, but could employ a speech writer to help with his defence. The Attic Orators therefore give us good information on some of these laws and how they would have been interpreted. They also provide a view of ancient Athenian society, how it was organised and the values of importance to them (Hunter, 1994). One such speech writer was called Lysias (c. 445- c. 380 BCE) who wrote a defence for a man named Euphiletus, who had murdered his wife’s lover. ‘On The Murder of Eratosthenes’ is a simple narrative of domesticity, deception and retribution, with a continued relevance to the present day. This hugely entertaining work also informs us of various aspects of Ancient Athenian society, including the role of women. So, let’s see what Euphiletus has to say for himself.

The Defence of Euphiletus

Euphiletus begins his defence by describing his early marriage, stating ‘when I decided to marry, Athenians, and brought a wife into my house, during the whole of that time my attitude was that I should neither harass her nor leave her too free to do whatever she wished’. He follows with ‘I watched her as far as possible, and paid as much attention to her as was reasonable’. They then had a child which seemed to cement their relationship: ‘I came to trust her and placed all my affairs in her keeping, thinking that we were now in the closest intimacy’. He self-consciously paints a picture of an ideal Athenian marriage, using hyperbole; ‘best wife in the world’, ‘so naïve as to think my wife the most virtuous in the city’. Was this what Euphiletus genuinely thought or was this to maximise the events that follow? Euphiletus is certainly self-conscious in the events he is relating, frequently directly addressing the jury as ‘gentlemen’ and otherwise adding asides; ‘for I must tell you these details’ and ‘I shall prove to you with strong evidence’. He presents himself as a rather hapless but good husband, and an upstanding citizen. He then describes how his wife had met her lover Eratosthenes at his mother’s funeral, and he had pursued her via her slave. Euphiletus states: ‘But when my mother passed away, her death became the cause of all my troubles, for it was when my wife attended her funeral that she was seen by this man, and was eventually corrupted by him’. Presenting himself as an unsuspecting husband, he describes this subterfuge as ‘passing on the proposals by which he ruined her’, ‘I thought nothing of this and had no suspicion’ and ‘I remained quite unaware of the wrongs being done to me’. However, one incident which indicates that possibly all was not entirely well with the marriage was a scene he describes when the baby was crying at night and Euphiletus told her to go and breastfeed the child. She replied ‘So that you can try your hand here with the little maid: once before, when you were drunk, you made a grab at her.’

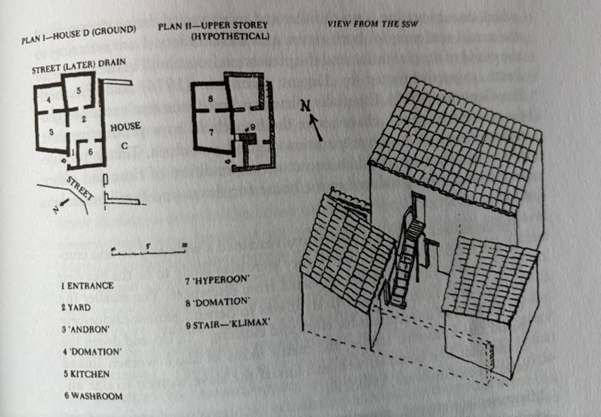

Euphiletus tells the jury of how he ignored various red flags regarding his wife’s behaviour, such as her wearing make-up despite being in mourning, and changing the family living arrangements so that her lover could have unfettered access to her. Women typically resided in the upstairs of a home and men stayed downstairs (presumably to thwart instances of infidelity or rape) and Euphiletus’s wife persuaded him with the rather flimsy excuse that she would find breastfeeding the baby easier if she were on the ground floor (Figure 2). Euphiletus then describes how he was later approached by an intermediary of an ex-lover of Eratosthenes, who informed him of his wife’s infidelity. These incidents suddenly made sense to him as pointers to his wife’s duplicity. Euphiletus has therefore portrayed himself as a simple, honest man, incapable of the later subterfuge he is accused of. Euphiletus tells how he then interrogated his wife’s slave who, under threat of being ‘whipped and sent to the mill’, confessed all.

Euphiletus then describes a trap he set for his wife and Eratosthenes. With his wife’s slave now firmly on his side, she woke him up when Eratosthenes next visited his wife. Euphiletus left the house and enlisted the help of several neighbours. All returned with torches to find Eratosthenes naked in bed with the wife. He was tied up and murdered, despite begging for mercy and offering a monetary settlement.

Euphiletus rounds off his defence with the consideration that the murder of Eratosthenes would act as a deterrent to others. He ends his defence by decrying the indignity of his trial in front of a jury of his peers, where his life and property were at stake, when he had simply been acting as a private citizen on behalf of the city.

The Verdict

Unfortunately, we rarely find out the result of cases written by the Attic Orators, as is the case of the murder of Eratosthenes. Here are a few salient points that may give an indication of how the jury may have decided and how this case informs us of Athenian life and the status of women in Athenian society.

- These were relatively elite citizen males. Euphiletus’s job is not mentioned but he was likely a farmer. Obtaining a speech writer would require funds and would have only been for those who could afford it. This has parallels to the modern world where there is the argument that the rich may evade justice simply due to being able to afford better legal counsel.

- In the Athenian household (oikos) the male head (kyrios) held the authority. In the case of a female this would be firstly her father, then her husband. We can see from the opening statements of Euphiletus that he initially kept his wife on a very short leash, trusting her more when she had a child. The Athenian wife’s place was firmly in the home and she was not permitted to venture out of the house except for religious events (Hunter, 1994: 9).

- The central claim of Euphiletus was that his wife had been corrupted by Eratosthenes. In Athenian law, the damage in rape or seduction cases was to the male guardian, not the woman. Therefore, the injured party was Euphiletus, rather than his wife. In Athenian society seduction was deemed to be more serious than rape (Edwards & Usher, 1985: 223). An adulterer could be punished by death if caught in the act or could pay compensation to the injured party i.e. Euphiletus (Cohen, 1991: 14 & 100).

- Athenian law punished intentional homicide with death or perpetual exile: these are the options Euphiletus was facing if found guilty. The central legal argument of Euphiletus is that the murder of Eratosthenes was justifiable homicide in Athenian law. Euphiletus claims to have been acting on behalf of the city on murdering Eratosthenes, but the crucial issue is whether he should have passed Eratosthenes to the authorities to try him and deliver punishment (Cohen, 1991: 14 & 100).

- This prosecution was likely to have been brought by the relatives of Eratosthenes, wishing for Euphiletus to be punished and/or a monetary settlement. They would have been emphasising the entrapment of Eratosthenes and his offer of monetary recompense.

- Various aspects of a slave’s role are described by Lysias. Euphiletus’s sexual interest in his wife’s slave was described but would have attracted little notice from the jurors; slaves were owned by their master and this could include sexual services. The slave of Euphiletus was threatened with physical violence and being sent to carry out a more difficult job. Slave testimony was commonly extracted under torture in a public place, with slaves having no right to appear as witnesses. Euphiletus makes no offer to make the slave available for public torture, as would be typical in a case such as this, so her third party evidence was obviously accepted (Hunter, 1994: 70-72).

- The wife of Euphiletus is not named. She is likely to have been subsequently divorced and returned to her father’s house. As a further punishment, she would have been excluded from attending religious events, which were the only means women had to participate in society. Her child would have remained under the control of Euphiletus (Cohen, 1991: 110).

Conclusion

To conclude, I think it likely that Euphiletus was much shrewder than the innocent husband he portrayed and set a trap for Eratosthenes to extract the ultimate revenge. However, with the assistance of the clever defence written by the speechwriter Lysias, he is likely to have escaped death or exile.

Many of the issues raised in ‘On The Murder of Eratosthenes’- such as infidelity, misogyny and legal accountability- have relevance to the present day, which is why this story remains as fresh and relatable as when it was created.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Lysias, The Killing of Eratosthenes in Greek Orators 1: Antiphon and Lysias, Edwards, M.J. and Usher, S. (trans) (1985), Oxford, Aris & Phillips.

- Lysias, On the Murder of Eratosthenes, Lamb, W. (trans.) (1930), London, William Heinemann Ltd. [Online]. Available at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0154 (Accessed 11 December 2024).

Secondary scholarship

- Cohen, D. (1991) Law, sexuality and society: the enforcement of morals in classical Athens, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Hunter, V. (1994) Policing Athens: Social Control in the Attic Lawsuits, 420-320 B.C, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

- Porter, J. (2007) ‘Adultery by the Book, Lysias 1 (On the Murder of Eratosthenes) and Comic Digesis’ in Carawan, E. (ed.) (2007) The Attic Orators, Oxford, Oxford University Press [Online]. Available at https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/50/article/651779/summary (Accessed 11 December 2024).

Leave a Reply