Introduction

Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE) is arguably Egypt’s most iconic Queen. She had love affairs with two of the most influential rulers of the Roman Empire of the time- Julius Caesar and Mark Antony- and was the last of the Ptolemaic rulers prior to Egypt’s annexation by Rome in 30 BCE. The theory that Cleopatra had a medical condition known as a goitre is mentioned in passing by both Tyldesley (2009: 62) and Fletcher (2008: 105). The presence of a goitre on a stone relief of Cleopatra is also noted by medical authorities (Leoutsakos, 2004; Sena, n.d.; Volpe and Sawin, 2022). However, this hypothesis remains uninvestigated and I would like to explore this further.

Discussions about Cleopatra’s appearance are generally centred around modern concepts of beauty, with modern viewers of Cleopatra’s coinage expressing disappointment with her large, hooked nose, pointed chin and flabby neck (Fletcher, 2008: 105). Her nose is in fact typical of coin depictions of previous Ptolemaic rulers: the ‘Ptolemaic nose’. Cleopatra’s appearance on coins therefore corresponds to the appraisal of the Roman historian Plutarch (Life of Antony 27.2) who described her as not a great beauty, but possessing an irresistible charm. An assessment of whether Cleopatra had a goitre is, unfortunately, hindered by a lack of contemporary depictions. However, we can examine the evidence that does exist in order to assess whether this was likely.

Medical Background

Firstly, what is a goitre (or goiter)? This is simply a medical term for an enlargement of the butterfly shaped thyroid gland in the neck. This has many causes, including cancer, autoimmune conditions and a lack of iodine, but most have no identifiable cause and are termed ‘simple goitres’. Affected individuals are usually female and often have a family history of goitre. The thyroid gland produces a hormone called thyroxine, which regulates an individual’s metabolism: a lack causes symptoms such as weight gain, lethargy and sluggishness and an excess causes symptoms such as weight loss, palpitations and anxiety. A goitre can be associated with either hypo or hyperthyroidism, or thyroxine levels can be normal. Tunny (2001) suggests a familial link to goitre in the Ptolemies, whereas Taylor (1978) suggests that the disease may have been endemic in the area, due to iodine deficiency.

The Evidence

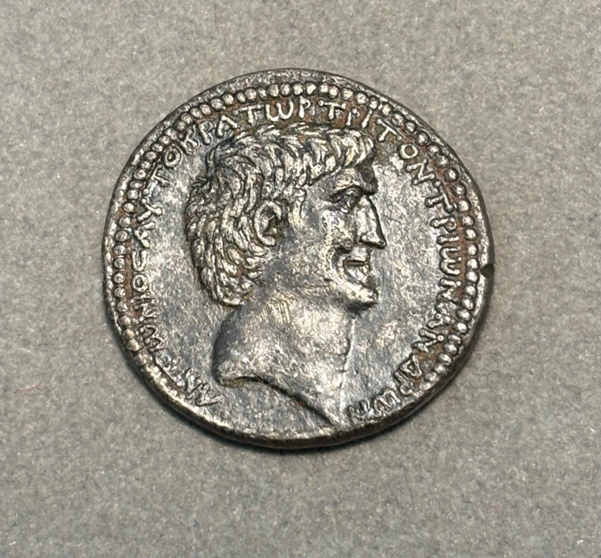

Unfortunately, depictions of Cleopatra are scarce. We have multiple depictions on coins, reliefs on the temple of Hathor in Dendera and several Roman busts and paintings which possibly depicted Cleopatra. Coin depictions are relatively robust due to the fact that the appropriate ruler is identified on the coin inscription. For political reasons, Cleopatra was depicted on coinage in an overtly Roman style: draped and diademed with a melon coiffure, and often wears a necklace and earrings. She has a large, hooked nose- the ‘Ptolemaic nose’. Some coins are quite degraded due to their age, and even relatively well-preserved coins will not always demonstrate a neck swelling. However, it is obvious on many depictions. Compare the modern photo of a patient with a goitre (Fig. 1) to the coin photos of Cleopatra in Figs. 2 and 3. The depictions in Figs. 3 and 4 are from a coin released by Cleopatra and Mark Antony near the end of their reign circa 36 BCE, when Cleopatra would have been in her mid 30s.

What could the artist have been attempting to depict on coinage if not a goitre? The obvious answer to this is simple obesity. We can see in Fig. 4 that Mark Antony has a thick neck indicating either a muscular or obese body habitus. This is quite different to the appearance of Cleopatra on the obverse of the coin, where she has a normal neck with an obvious butterfly shaped swelling: effectively an anatomically correct goitre. In antiquity, obesity in coins was often depicted as a favourable feature and was a frequent depiction of the Ptolemaic dynasty. This was termed tryphe and its association with conspicuous consumption was much derided by the Romans. Depictions on coinage took the form of so called ‘rings of Venus’ indicating good health and wealth. This is demonstrated on an early coin depiction when Cleopatra was around nineteen, shown in Fig. 5. However, this is a markedly different appearance to her depictions on Figs. 2 and 3.

Do any other depictions of Cleopatra help with our hypothesis that she had a goitre? Cleopatra was depicted on stone reliefs in the Temple of Hathor in Dendera. However, these reliefs are rather more problematic than her coin depictions.

The relief in Figure 6 is one which is typically cited as representing Cleopatra by medical sources (Leoutsakos, 2004; Sena, n.d.; Volpe and Sawin, 2022). Unfortunately, this is actually a representation of the goddess Isis, and the cartouche of Cleopatra is a modern forgery, having been added to a plaster cast of the original scene by a curator at Cairo Museum (Tyldesley, 2009: 122-124). This depiction has therefore been excluded from my analysis.

Another relief from the Temple of Hathor in Dendera (Fig.7) more reliably represents Cleopatra and her son Caesarion making offerings to the gods. The circular neckline of her gown may give the impression of some neck swelling, but the appearance is largely unconvincing.

Similarly, various marble Roman busts, paintings and statues exist which are believed to depict a young Cleopatra. One example is a marble bust in Berlin (Fig. 8). As these art works cannot be definitively identified as being Cleopatra VII, I have not included them as evidence.

Possible Symptoms

If Cleopatra did have a goitre, what symptoms could she have experienced? This could have been an asymptomatic goitre and she would have had no associated symptoms. If this goitre was due to thyroid cancer, her disease would have progressed leading to her early death within a few years. If she had been hypothyroid, she would have been extremely lethargic with weight gain, and if hyperthyroid she would have had symptoms such as weight loss, palpitations and anxiety. Both hypo and hyper thyroidism would have ensured that Cleopatra would have had poor health and may have struggled in the day to day governing of her country.

Are there any clues regarding Cleopatra’s health from written sources? Unfortunately, Cleopatra’s history was the subject of hostile propaganda from Roman historians, who wished to portray her as a temptress who seduced the upstanding Roman Mark Antony in order to avoid any suggestion of civil war between Octavian and Mark Antony. Plutarch (Life of Antony 53.3-4) discusses an episode where Cleopatra was anxious about Antony returning to his Roman wife Octavia. Cleopatra was obviously being watched closely, and her anxiety and tearfulness were interpreted as cunning and manipulative behaviour in order to secure Antony’s affection. Her associated weight loss was interpreted as an attempt to make herself slender and desirable to him. Could this episode have simply been one of anxiety and weight loss due to a thyrotoxic crisis which was then negatively interpreted by Roman historians? It is impossible to be certain.

Conclusion

To conclude, it is clear that there is good numismatic evidence that Cleopatra did have a goitre, but unfortunately no other supporting visual evidence exists. The fact that Cleopatra was not consistently depicted with a goitre on coins is not necessarily problematic- a goitre typically develops in females aged 30 plus, which would explain the depiction on the coin of Cleopatra and Mark Antony which was released in the later stages of her rule. This goitre may have caused her significant health issues which would have affected her ability to rule and ultimately may have led to an early natural death.

Bibliography

Primary sources:

- Plutarch, Life of Antony, in Pelling, C. (ed.) (1988), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Plutarch, Life of Antony, in Perrin, B. (ed.) (1920), Perseus [Online]. Available at https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0007 (Accessed 22 November 2024).

Secondary scholarship:

- Bradley, M. (2011) ‘Obesity, Corpulence and Emaciation in Roman Art’, Papers of the British School of Rome, Vol. 79 [Online]. Available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/B5F34877E503D25C67792AD21DC13172/S0068246211000018a.pdf/obesity-corpulence-and-emaciation-in-roman-art1.pdf (Accessed 12 November 2024).

- Fletcher, J. (2008) Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend, London, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Leoutsakos, V. (2004) ‘A short history of the thyroid gland’, Hormones: International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 3(4), pp.268-271 [Online]. Available at http://www.hormones.gr/115/article/article.html (Accessed 12 November 2024).

- Roller, D. (2010) Cleopatra: A Biography, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Sena, L. M. (n.d.) The Thyroid in Art [Online]. Available at https://search.app/aV1nW4XiPgjxnA4R7 (Accessed 24 November 2024).

- Taylor, G. (1978) ‘The Other Cleopatra’, Arab and Islamic Cultures and Connections, vol. 29, no. 2, March/April 1978 [Online]. Available at https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/197802/the.other.cleopatra.htm (Accessed 12 November 2024).

- Tunny, J. (2001) ‘The Health of Ptolemy II Philadelphus’, The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists, vol.38, no1/4, pp.119-34 [Online]. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/24519771 (Accessed 12 November 2024).

- Tyldesley, J. (2009) Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt, New York, Basic Books.

- Varotto, E., Galassi, F. (2019) ‘A likely representation of goiter in Antonio Canova’s Helen of Troy’, Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 42, pp.1389-1390 [Online]. Available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40618-019-01080-z (Accessed 12 November 2024).

- Volpe, R., Sawin, C. (2022) ‘The history and iconography relating to the thyroid gland’ in Wass, J. and Stewart, P. (eds.) (2022) Oxford Textbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes (3rd. ed.), Oxford, Oxford Academia [Online]. Available at https://academic-oup-com.ezproxy1.lib.gla.ac.uk/book/37215/chapter/327537995 (Accessed 15 November 2024).

Leave a Reply